To Swivel or to Twist, That is The Question

By Captains Alex & Daria Blackwell

To a cruiser, anchoring tackle is perhaps one of the most

important pieces of gear – second only to the boat itself. As such, any mention

of the pros or cons of any particular component or configuration will

inevitably lead to some pretty strong opinions. We should know, having written Happy

Hooking – the Art of Anchoring, though highly acclaimed and as impartial as

we felt able to make it, our book, and subsequent articles have stirred up the

occasional hornet’s nest of ‘discussion’.

So it was with our chapter on swivels. To date we have

shunned them, viewing swivels as an unnecessary weak link in the components

connecting the sea bed to our boat. Yes, we have swung at anchor for weeks at a

time while cruising. Where the wind was heavy, our anchor veered as a good

anchor should. In light wind situations we did note that our chain was occasionally

twisted, but this always corrected itself when we weighed anchor. The twist

cannot get past the toothed wildcat on our windlass, so there is no chance that

the twisted chain would find its way into our chain locker. The anchor simply

spins while coming up and any twist is straightened out.

Another reason many people opt for a swivel is that they

fear that the protruding shackle pin might get stuck on the bow roller when

deploying or weighing anchor. Unless the bow roller assembly has been very

poorly designed, this should not be an issue. We have literally anchored

thousands of times sometime two or three times in one day and have never seen

this happen.

|

There is one place we do have a swivel – on our mooring.

There is a fairly stiff tidal current where our boat is moored. Our boat thus

swings a lot. As our mooring cannot veer, it is conceivable that our riser,

which is part chain and part arm thick nylon, would become twisted over the

course of the year. We have therefore incorporated a heavy galvanised swivel in

the riser, which we do replace every year. So, one cannot say that we are

anti-swivel. |

Swivel failure

We were cruising in company with some friends one weekend

a while back. When our two boats reached the destination, we dropped our hook

and got to work preparing the cocktails we had promised our friends. We heard a

shout and found our friends had brought their boat alongside ours. They wanted

to raft up. This was odd, as we had discussed anchoring separately, so that our

respective boats would be secure for the night. It turned out that they had

lost their shiny stainless steel anchor (of which we had been quite envious) from

their bow when a stainless steel swivel failed while underway.

Two things became evident as we looked at their problem.

There was some corrosion (rust) on their ‘stainless steel’ swivel – yes,

stainless steel will rust.(see below note on stainless steele) And there was significant evidence of rust on the

swivel shaft, which was hidden from view, as is the case with many of the

‘nicer’ swivels on the market today. |

|

The problem with all of these swivels

is that their shaft is hidden from view. Should the shaft rust, which would

seem to be likely as the space around it will remain moist, then it will no

longer be as strong as it once was.

|

Some of these swivels have a threaded shaft with a nut

welded onto it to hold the two bits together. First of all, a threaded bar (as

with the one above that snapped) is inherently weaker than a solid bar of the

same diameter. Then there is the issue of the welds not holding, as happened in

the swivel shown here. |

The other problem we found was that our friends were in

the habit of bringing their anchor in tight to the bow roller using their

windlass – their chain was thus bar taut. They did this so that their anchor

would not bounce around while underway. Given the fact that there will

inevitably be movement as the boat pounds through waves, this will undoubtedly

put undue strain on the swivel, any shackle, and on the windlass. |

|

|

Our friends quickly purchased a new anchor and swivel and

were once again the envy of the fleet. A few short weeks later, both were gone.

Having reflected on what had happened, they now have a galvanised anchor and no

swivel. They also tie their anchor off to a cleat leaving their chain loose on

the foredeck. We just heard that they have been successfully using this same

setup for several years now. |

Photo John Harries |

Another reported failure of this type of swivel occurs

when the boat veers strongly to one side and then comes up short. In this

instance something has to give. These lateral loads can be so great as to bend

the anchor shaft. They can also cause the swivel to be bent open with the screw

thread being stripped out as is shown in the photo to the left. Alternatively the

swivel shaft may shear or, as in the example to the right, the internal

retaining pin may break. Of course this lateral load is also applied as the

anchor is hauled over the bow roller – often with some gusto, so that the

anchor bounces with the swivel on the roller as it rotates into the correct

orientation. |

|

|

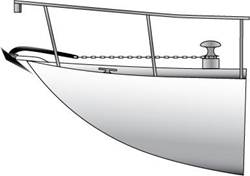

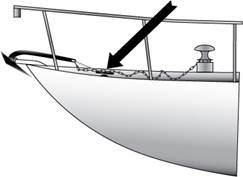

A solution to this is to position the swivel some way up

the chain as is suggested by Craig Smith (Rocna.com). A short piece of chain is

thus shackled to the anchor with the swivel connecting it to the rest of the

chain rode. But this leaves you with the shackle that some wish to eliminate. |

The other option is to design the swivel so that it can

indeed move laterally as well as twist. One such example is shown here, where

the manufacturer has designed in what amounts to an extra chain link. It would

appear that the lateral forces would still be exerted on the jaws attaching to

the anchor and on the swivel shaft – not to mention that the shaft remains

hidden from view and subject to rusting. |

|

|

Following the adage that simple is better, one might also

consider a simple shackled on swivel. The one we saw here could move laterally

if sized correctly. Its only downside is, of course, that the shaft is still

obstructed from view. |

For anyone thinking they need a swivel, and that they need

to attach it to the anchor, there is one option we had the pleasure of taking

out cruising for the past several months. It is the Ultra flip swivel manufactured

in Turkey by Boyut Marine. It incorporates a flipping nub to assist anchor

alignment, a durable Teflon-coated ball for easy rotation, and a back bridge

that supports the anchor as it travels over the roller. The back bridge also

looks like it would add extra strength to the already beefy swivel. This swivel

also has virtually no hidden places that cannot be inspected and for moisture

to collect causing corrosion. The other part we liked was that this swivel not

only twists, but will articulate to all sides reducing the danger of the

lateral load. Like the beautifully styled Ultra anchor, Boyut has again

produced a lovely looking piece of equipment as well. |

|

A note on stainless steel shackles and swivels.

Stainless steel looks great. We were indeed very envious of

our friend’s lovely shiny tackle particularly when next to our own dull

galvanized anchor and chain. Even our shackles are dull, boring looking

galvanized iron. On the other hand stainless steel, even the top grade 316, is

more brittle, and thus not as strong as so called mild steel. Another chief

characteristic of stainless steel is that it is smooth (and shiny). Galvanized

shackles are rough and will bind when tightened properly. They can be difficult

to open and are thus quite unlikely to ever open when they shouldn’t. Stainless

steel shackles, on the other hand, do not bind and may come undone when least

expected. This happened to me at the top of the mast when the shackle

connecting my climbing gear to the halyard opened (but that is another story).

Stainless steel shackles must thus always be seized with wire.

Stainless steel Rusts

The chromium in stainless steel creates a passivation layer on the surface that protects the steel from rusting. In low oxygen situations and/or warm water this passivation layer breaks down and corrosion will set in. Low oxygen will occur in crevasses which stary wet (cracks, welds, shackle threads, keel bolts, etc.) or confined spaces (swivel shafts, etc.). Corrosion may also happen internally. Welding may cause the cromium to bind with carbon and thus indirectly lead to corrosion.

We discuss this in greater deal in the upcoming third edition of Happy Hooking.

So, where does this all leave us?

With the Ultra swivel we have indeed been shown a swivel

that appears to have very elegantly solved all the arguments we would put

forward in opposition of using a swivel on an anchor rode. It obviates the need

for a shackle, it has no hidden parts, it looks to be very strongly (and

beautifully) constructed, and it moves laterally as well as twisting.

Does this mean that it is advisable to add a swivel to an

anchor rode? The way we see it, not really. As mentioned, we have on occasion spent

months at anchor with wind and tide shifts. Our rode certainly had twists in

it, but they all came out as we weighed anchor. With a permanent mooring, that

is certainly a different matter, and a local mooring contractor would be the

best to advise on this.

In the final analysis, it remains up to the individual

boater. There is good quality equipment available. So, if you feel you must go

this way, then go you may!